Using the Quadrilateral Without Losing the Plot

The Wesleyan Quadrilateral sounds like something from geometry class or a sci-fi map.

But it’s actually a modern attempt to describe how Christians—especially in the Wesleyan tradition—think theologically.

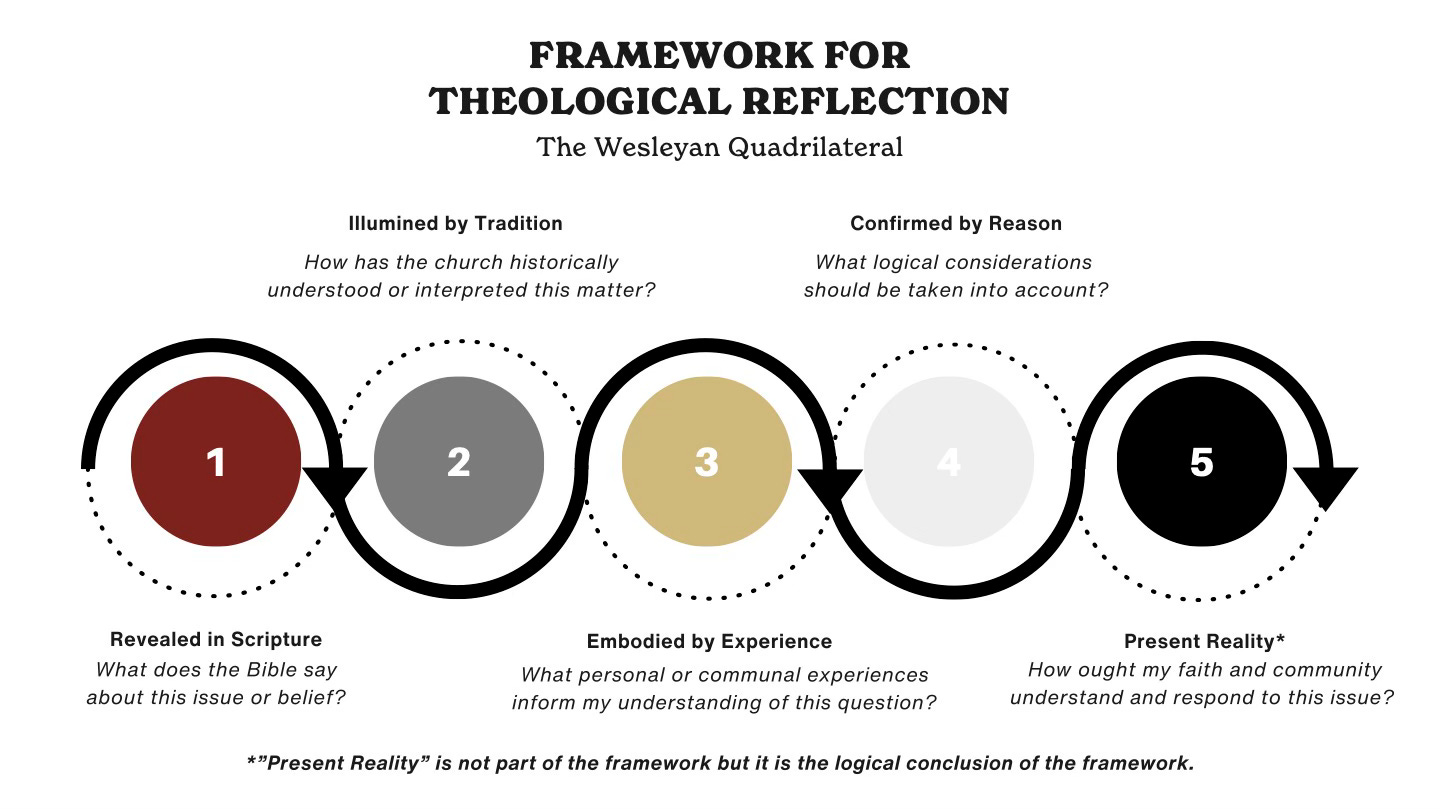

The term was coined by 20th-century theologian Albert Outler, who observed that John Wesley frequently drew upon four sources in his theological reflection: Scripture, tradition, reason, and experience.

That observation eventually led to a model—a framework.

There are issues with the framework, something David F. Watson points out in his article.1 For one thing, Wesley never actually laid this out—no cool Canva slides, no quadrilateral doodles in the margins of his journals. Even Outler later grew uneasy with how people started treating it.

Sure, Wesley leaned heavily on Scripture and drew from tradition, reason, and experience to make better sense of what the Bible said. But if we’re being more accurate, it’s better to think of it not as four equal sources, but as Scripture taking the lead, with tradition, reason, and experience playing supporting roles—a trilateral hermeneutic (tradition, reason, experience) orbiting around a unilateral authority (Scripture).2

Watson thinks we should stop using the Quad. He argues that the better guiding principles for theological reflection are divine revelation, divine guidance, and doctrinal consensus when approaching theological questions. Divine guidance and divine presence are theological realities, not just conceptual ones.

We’re not building theology from scratch. We’re responding to Someone who has already spoken first. God making himself known through creation, through Christ, through Scripture, and, yes, through the ongoing guidance of the Spirit in the life of the church.

Revelation comes first. The other stuff helps us work it out.

In other words, we let Scripture function as revelation, not just data to interpret through our clever framework.

I actually agree with him.

Still, for those just beginning to think theologically—students, lay leaders, and curious skeptics—this kind of ordered framework (the Quad) can help develop the instincts of good reflection.

It’s a way to practice asking better questions and resisting simplistic answers. It invites the person to listen carefully to Scripture, reflect honestly on the Great Tradition, and remain attentive to reason and experience—all while keeping divine revelation and divine guidance as guiding principles for theological development.

No model can do the heavy lifting of actually knowing God—the God who reveals, guides, and calls his people to faithful witness The real danger is when a framework (even a well-meaning one) becomes the point, as if the goal of theology were to master the system instead of be transformed by the God we reflect on, speak to (and about), and dare to write about. But if it nudges us deeper into the life of the triune God and the beautiful life of the church, then it’s done its job.

The real value of the Quadrilateral is pedagogical. It’s not properly a “theological method” (I’ll discuss that in a later post). The Quadrilateral is a tool for catechesis, for learning what’s involved in forming our theology in the first place.

I still use the Quadrilateral—and I even teach it, especially to folks just starting out in theological reflection. For all its flaws, it sparks a conversation about what shapes our beliefs and how we come to understand God, Christ, and life in the Spirit.

Just remember: use the Quad, don’t lose the plot.

David F. Watson, “The Global Methodist Church and the Quadrilateral,” Firebrand (2023).

Randy L. Maddox, Responsible Grace: John Wesley’s Practical Theology (Nashville: Abingtdon, 1994), 46.